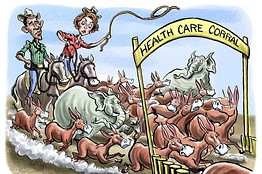

Can Nancy Pelosi Get the Votes?

The Senate bill's abortion language is not the House Speaker's only problem.

By

MICHAEL BARONE

WSJ.com

Are there enough votes in the House to pass the Senate's health-care bill? As of today, it's clear there aren't. House Democratic leaders have brushed aside White House calls to bring the bill forward by March 18, when President Barack Obama heads to Asia. Nevertheless, analysts close to the Democratic leadership tell me they're confident the leadership will find some way to squeeze out the 216 votes needed for a majority.

Speaker Nancy Pelosi has indeed shown mastery at amassing majorities. But it's hard to see how she'll do so on this one. The arithmetic as I see it doesn't add up.

The House passed its version of the health bill in November by 220-215. Of those 220, one was a Republican who now is a no. One Democrat who voted yes has died, two Democrats who voted yes have resigned, and one Democrat who voted no has resigned as well. So if everyone but the Republican votes the way they did four months ago, the score would be 216-215.

But not everyone is ready to vote that way. The House bill included an amendment prohibiting funding of abortions sponsored by Michigan Democrat Bart Stupak. The Senate bill did not. Mr. Stupak says he and 10 to 12 other members won't vote for the Senate bill for that reason. Others have said the same, including Minnesota's James Oberstar, chairman of the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, and Dan Lipinski, a product of the Chicago Democratic machine.

Mrs. Pelosi may have some votes in reserve—members who would have voted yes if she needed them in November and would do so again. But we can be pretty sure she doesn't have more than 10, or she wouldn't have allowed the Stupak amendment to come forward at the last minute the first time. She also might get one or two votes from members who voted no and later announced they were retiring.

But that's not enough—and there are other complications. Voting for the Senate bill means voting for the Cornhusker kickback and the Louisiana purchase—the price Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid paid for the votes of Ben Nelson and Mary Landrieu. It's not hard to imagine the ads Republicans could run attacking House members for sending money to Nebraska and Louisiana but not their home states.

To be sure, Democratic leaders say they want to repair the Senate bill by subsequent legislation that could be passed with 51 votes in the Senate under the reconciliation process. But they have yet to produce such a bill. It can't include the Stupak amendment, which experts say doesn't qualify for the reconciliation process. And there's no way they can credibly promise the Senate will pass it. Senate rules allow many forms of obstruction. The reconciliation process is littered with traps.

There is also the House's historic lack of trust in the Senate, which is on display by Democrats who voted yes in November. "No, I don't trust the U.S. Senate," Wisconsin's Steve Kagen told WLUK-TV in Green Bay, this week. New York's Dan Maffei was quoted in the Syracuse Post-Standard on Monday that "I will trust the president, but I will not trust the Senate."

"I am not inclined to support the Senate version," Nevada's Shelley Berkley told the New York Times last week. "I would like something more than a promise. The Senate cannot promise its way out of a paper bag." Her district voted 64% for Barack Obama.

Other Democrats who voted yes seem to be wavering. "I don't think reconciliation is a good idea," Indiana's Baron Hill was quoted recently in Bloomberg News. New York's Michael Arcuri says he's a no for now. "There would have to be some dramatic changes in it for me to change my position," he recently told the Utica Observer-Dispatch.

"I think we can do better," California's Dennis Cardoza told the New York Times last week. "If the Senate bill is not fixed, that"—voting no—"is not a flip-flop," Nevada's Dina Titus told the Las Vegas Review-Journal last week. "I see that as standing by your convictions." Most of these members represent districts which went Republican some time in the past decade—and could easily do so again if national polls are an indicator.

There's a more fundamental problem for the Democratic leadership: Their majority is not as strong as their 253-178 margin suggests.

A Democratic House majority tends to have fewer members with safe seats than a Republican majority. Consider that in 2005 Speaker Dennis Hastert had 214 Republican members elected in districts Mr. Bush carried, just four seats short of a majority. Today Speaker Nancy Pelosi has 208 Democratic members elected in districts Mr. Obama carried, eight seats short of a majority.

The Democratic bedrock is actually slightly smaller than the Republican bedrock was four years ago, even though the Democrats have 31 more members. That's partly because of Republican gerrymandering earlier in the decade, but it's more because Democratic voters tend to be bunched in relatively few districts. Mr. Obama carried 28 districts with 80% or more; John McCain didn't reach that percentage in any district.

A lot of Democrats—most Black Caucus members and many "gentry liberals" (to use urban scholar Joel Kotkin's term) like Mrs. Pelosi—are elected in overwhelmingly Democratic districts. This means there aren't that many faithful Democratic voters to spread around to other seats.

As a result, more than 40 House Democrats represent districts which John McCain carried. Most voted no in November and would presumably be hurt by switching to yes now. Moreover, Mr. Obama's job approval now hovers around 48%, five points lower than his winning percentage in 2008. His approval on health care is even lower.

Another 32 House Democrats represent districts where Mr. Obama won between 50% and 54% of the vote, and where his approval is likely to be running under 50% now. That leaves just 176 House Democrats from districts where Mr. Obama's approval rating is not, to borrow a real-estate term, under water. That's 40 votes less than the 216 needed.

"If there is a path to 216 votes, I am confident the Speaker will find it," writes Bush White House legislative strategy analyst Keith Hennessey on his blog. "She has a remarkable ability to bend her colleagues to her will." True, but perhaps that ability has led Democrats in the White House and on Capitol Hill to embark on what will be remembered as a mission impossible.

Mrs. Pelosi, whom I have known for almost 30 years, may turn out to be even shrewder than I think. But she may be facing a moment as flummoxing as the one when Democratic Speaker Thomas Foley lost the vote on the rule to consider the crime and gun control bill in August 1994, or when Republican Speaker Dennis Hastert saw the Mark Foley scandal explode on the last day of the session in September 2006. Both were moments when highly competent and dedicated House speakers saw their majorities shattered beyond repair.

That moment, if it comes, will occur some time between now and the Easter recess. The Democrats' struggle to get 216 votes is high stakes poker.

Mr. Barone is senior political analyst for the Washington Examiner,

resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and co-author of "The

Almanac of American Politics 2010" (National Journal).