Now for the Slaughter

On the road to Demon Pass, our leader encounters a Baier.

By Peggy Noonan

WSJ.com

Excuse me, but it is embarrassing—really, embarrassing to our country—that the president of the United States has again put off a state visit to Australia and Indonesia because he's having trouble passing a piece of domestic legislation he's been promising for a year will be passed next week. What an air of chaos this signals to the world. And to do this to Australia of all countries, a nation that has always had America's back and been America's friend.

How bush league, how undisciplined, how kid's stuff.

You could see the startled looks on the faces of reporters as Press Secretary Robert Gibbs, who had the grace to look embarrassed, made the announcement on Thursday afternoon. The president "regrets the delay"—the trip is rescheduled for June—but "passage of the health insurance reform is of paramount importance." Indonesia must be glad to know it's not.

The reporters didn't even provoke or needle in their questions. They seemed hushed. They looked like people who were absorbing the information that we all seem to be absorbing, which is that the wheels seem to be coming off this thing, the administration is wobbling—so early, so painfully and dangerously soon.

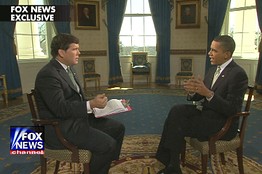

Thursday's decision followed the most revealing and important broadcast interview of Barack Obama ever. It revealed his primary weakness in speaking of health care, which is a tendency to dodge, obfuscate and mislead. He grows testy when challenged. It revealed what the president doesn't want revealed, which is that he doesn't want to reveal much about his plan. This furtiveness is not helpful in a time of high public anxiety. At any rate, the interview was what such interviews rarely are, a public service. That it occurred at a high-stakes time, with so much on the line, only made it more electric.

I'm speaking of the interview Wednesday on Fox News Channel's "Special Report With Bret Baier." Fox is owned by News Corp., which also owns this newspaper, so one should probably take pains to demonstrate that one is attempting to speak with disinterest and impartiality, in pursuit of which let me note that Glenn Beck has long appeared to be insane.

That having been said, the Baier interview was something, and right from the beginning. Mr. Baier's first question was whether the president supports the so-called Slaughter rule, alternatively known as "deem and pass," which would avoid a straight up-or-down House vote on the Senate bill. (Tunku Varadarajan in the Daily Beast cleverly notes that it sounds like "demon pass," which it does. Maybe that's the juncture we're at.) Mr. Obama, in his response, made the usual case for ObamaCare. Mr. Baier pressed him. The president said, "The vote that's taken in the House will be a vote for health-care reform." We shouldn't, he added, concern ourselves with "the procedural issues."

Further in, Mr. Baier: "So you support the deem-and-pass rule?" From the president, obfuscation. But he did mention something new: "They may have to sequence the votes." The bill's opponents would be well advised to look into that one.

Mr. Baier again: So you'll go deem-and-pass and you don't know exactly what will be in the bill?

Mr. Obama's response: "By the time the vote has taken place, not only will I know what's in it, you'll know what's in it, because it's going to be posted and everybody's going to be able to evaluate it on the merits."

That's news in two ways. That it will be posted—one assumes the president means on the Internet and not nailed to a telephone pole—should suggest it will be posted for a while, more than a few hours or days. So American will finally get a look at it. And the president was conceding that no, he doesn't know what's in the bill right now. It is still amazing that one year into the debate this could be true.

Mr. Baier pressed on the public's right to know what is in the bill. We have been debating the bill for a year, the president responded: "The notion that this has been not transparent, that people don't know what's in the bill, everybody knows what's in the bill. I sat for seven hours with—."

Mr. Baier interrupts: "Mr. President, you couldn't tell me what the special deals are that are in or not today."

Mr. Obama: "I just told you what was in and what was not in."

Mr. Baier: "Is Connecticut in?" He was referring to the blandishments—polite word—meant to buy the votes of particular senators.

Mr. Obama: "Connecticut—what are you specifically referring to?"

Mr. Baier: "The $100 million for the hospital? Is Montana in for the asbestos program? Is—you know, listen, there are people—this is real money, people are worried about this stuff."

Mr. Obama: "And as I said before, this—the final provisions are going to be posted for many days before this thing passes."

Mr. Baier pressed the president on his statement as a candidate for the presidency that a 50-plus-one governing mentality is inherently divisive. "You can't govern" that way, Sen. Obama had said. Is the president governing that way now? Mr. Obama did not really answer.

Throughout, Mr. Baier pressed the president. Some thought this bordered on impertinence. I did not. Mr. Obama now routinely filibusters in interviews. He has his message, and he presses it forward smoothly, adroitly. He buries you in words. Are you worried what failure of the bill will do to you? I'm worried about what the status quo will do to the families that are uninsured . . .

Mr. Baier forced him off his well-worn grooves. He did it by stopping long answers with short questions, by cutting off and redirecting. In this he was like a low-speed bumper car. In the end the interview seemed to me a public service because everyone in America right now wants to see the president forced off his grooves and into candor on an issue that involves 17% of the economy. Again, the stakes are high. So Mr. Baier's style seemed—this is admittedly subjective—not rude but within the bounds, and not driven by the antic spirit that sometimes overtakes reporters. He seemed to be trying to get new information. He seemed to be attempting to better inform the public.

Presidents have a right to certain prerogatives, including the expectation of a certain deference. He's the president, this is history. But we seem to have come a long way since Ronald Reagan was regularly barked at by Sam Donaldson, almost literally, and the president shrugged it off. The president—every president—works for us. We don't work for him. We sometimes lose track of this, or rather get the balance wrong. Respect is due and must be palpable, but now and then you have to press, to either force them to be forthcoming or force them to reveal that they won't be. Either way it's revealing.

And so it ends, with a health-care vote expected this weekend. I wonder at

what point the administration will realize it wasn't worth it—worth the discord,

worth the diminution in popularity and prestige, worth the deepening of the

great divide. What has been lost is so vivid, what has been gained so amorphous,

blurry and likely illusory. Memo to future presidents: Never stake your entire

survival on the painful passing of a bad bill. Never take the country down the

road to Demon Pass.