On Track To Become Next U.K.?

Public Spending: Government gobbled up the British economy with amazing speed in the past decade. Here's how it happened — and why something very much like it could happen in the U.S.

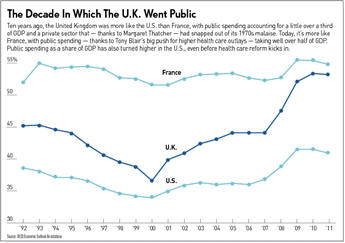

It was not so long ago that Great Britain was rightly seen as the most "American" of the major European economies, with a tilt toward free-market capitalism and a relatively lean public sector.

No more. The U.K. is now, in the words of the Cato Institute's Daniel J. Mitchell, "the new France." Its public-sector spending has exploded over the past decade so that it now makes up more than half the economy.

According to the latest figures from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, government spending was 52.1% of Britain's GDP in 2009. The OECD projects the public sector to hit 53.2% of GDP in 2011.

That would leave the U.K. just a tad behind the traditionally state-dominated French economy, where government made up 55.5% of GDP in 2009 and is expected to be 54.8% in 2011. But Britain would have far more in common with France than with the U.S., where the GDP share of public spending hit 41.5% in 2009 and is expected to fade to 40.9% next year.

A decade ago, the U.K. had far more in common with the U.S. than with its Continental counterparts. Its public spending then was 36.6% of GDP, compared with 33.9% in the U.S. and 51.6% in France. It also could point to remarkable success in reviving its private sector from the deep malaise of the 1970s and shrinking the government's economic footprint to levels not seen since the early 1960s.

Margaret Thatcher did much of this work, but Tony Blair carried on the mission in his first term as prime minister, back when "New Labour" was more than just a slogan.

But something happened around 2000 to turn the tide back in favor of the public sector. Perhaps Blair could no longer restrain Labour's big-government instincts. Maybe he was too confident about Britain's capacity to pay for new public spending through economic growth.

Whatever the motives, what happened is clear. The public sector hit the gas at the start of the decade and started growing beyond expectations.

And here's an ominous twist: Health care was clearly a factor in the spending spree. Blair's 2000 budget set out explicitly to boost inflation-adjusted spending on the National Health Service by 6.1% over the next four years. This was to be "the longest period of sustained high growth in the history of the NHS." The government kept that promise, raising health spending by about 9% a year (pre-inflation) through 2005.

In those five years, the government share of GDP soared by more than six percentage points to 43.1%. That wasn't part of the plan. The 2000 budget predicted that public-sector spending would rise just a bit to 37.2% in 2005.

How could the government guess so wrong? The short answer is that this is what governments usually do in budget projections. Except for rare surprises such as the surpluses of the late 1990s, they chronically underestimate the growth potential of the welfare state.

This isn't just a British syndrome. Washington has created some big upside spending surprises too. Medicare and Medicaid probably would never have made it through Congress if their future growth had been predicted accurately.

The George W. Bush administration was no better than Blair's at foretelling the fiscal future. In 2001, it forecast federal spending of $2.7 trillion, or 15% of the economy, in 2011. That wasn't even close. The federal share of GDP was 20.7% by 2008, Bush's last full year in office. Recession and "stimulus" spending pushed it to 24.7% in 2009.

Under the Obama administration's 2011 budget, Washington is due to spend $3.8 trillion, or 25% of the economy. The Obama budget forecasts a drop in federal outlays to 22.9% of GDP by 2015. Further out, the Congressional Budget Office says federal spending will be about 24% of GDP in 2020 under the Obama budget.

Adding the roughly 18% in GDP that goes to state and local spending, this would give us a public sector of 42% a decade from now.

That's high enough by historical standards in this country. But there's reason to believe that the actual growth in government will be much more. Obama has just engineered a big new entitlement by extending health insurance to some 30 million Americans. And this is supposed to be paid for, in large part, by cuts in Medicare, a politically sacrosanct entitlement.

Good luck with that. By a rule of thumb born of bitter experience,

it's wise to add a half-dozen or so percentage points, or even more, to

those public-sector projections five or 10 years out. If the rule holds,

we're already on the track followed by the U.K. over the past 10 years.

Before long, we may become the next new France.